Very Preterm Infants and RSV

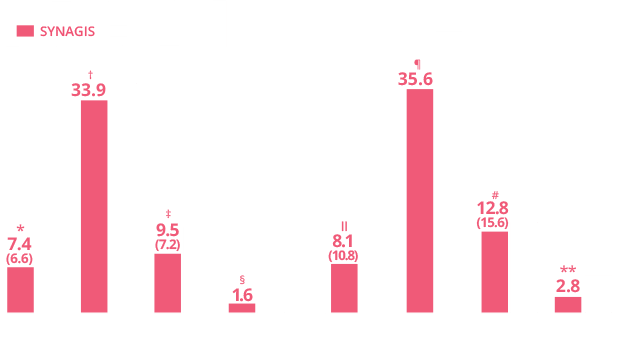

SYNAGIS® reduces RSV hospitalization severity among very preterm infants1

INFANTS LESS THAN 29 wGA ARE AT THE HIGHEST RISK FOR SEVERE RSV DISEASE AND HOSPITALIZATION2-4

IN A REAL-WORLD STUDY

SYNAGIS reduced RSVH severity among very preterm infants in the outpatient setting1

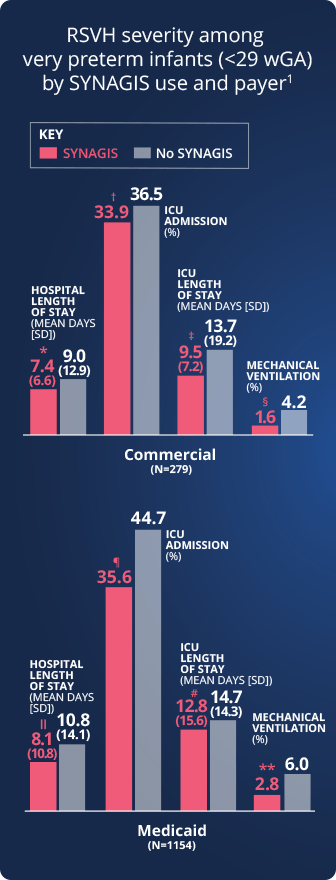

RSVH severity among very preterm infants (<29 wGA)

by SYNAGIS use and payer1

RSVH severity was measured by

RSVH-related length of hospital stay

Rates of ICU

admission

ICU length

of stay

Rates of mechanical

ventilation

*P<0.001 vs infants who received SYNAGIS;

†P=0.667; ‡P=0.008; §P=0.200; IIP=0.019; ¶P=0.002;

#P=0.191; **P=0.007.

Review the additional pivotal IMpact-RSV trial data, which established the efficacy and safety of SYNAGIS in preterm infants with and without BPD.5,6

Real-world Study Design

RSVH and RSVH characteristics were compared in very preterm (<29 wGA) and term (>37 wGA) infants.1

Using the MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid administrative claims databases, infants born between July 1, 2003, and June 30, 2020, were identified and classified as very preterm (N=40,123) or term (N=4,421,942). Infants with evidence of health conditions such as congenital heart disease and cystic fibrosis were excluded. During the 2003 through 2020 RSV seasons (November to March), claims incurred by infants while they were <12 months old were evaluated for outpatient administration of SYNAGIS and RSVH.1

Primary objective: To characterize outpatient SYNAGIS prophylaxis and risk of RSVH among very preterm infants and to compare the course of RSVH among these infants.1

Study limitations: This study used retrospectively collected administrative claims data, which could contain coding errors and omission of unbilled/over-the-counter services. Data on inpatient administration of SYNAGIS was not available in the database; only outpatient administrations were measured. Some infants in the subgroup without outpatient SYNAGIS use may have received SYNAGIS during the birth hospitalization or a subsequent hospitalization, possibly resulting in misclassification error. RSVH may have occurred in some infants prior to SYNAGIS administration. In addition, infants with a single outpatient dose of SYNAGIS were included, although the recommended dosing interval is monthly. The study was restricted to commercially insured and Medicaid-insured infants.1

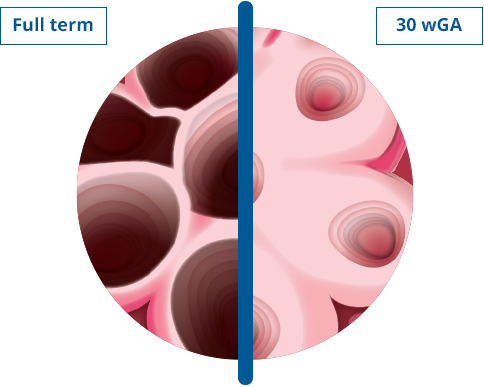

Interrupted lung development compromises lung capacity in preterm infants2

The small airways of very preterm infants are easily obstructed by the infectious process associated with RSV disease.2-4

Use this tool to compare estimates of lung capacity by gestational age.

- 34% of lung volume

versus full-term infants

(60 mL vs 180 mL) - 26% of the lung surface area

versus full-term infants

(1.19 m2 vs 4.55 m2) - 66% thicker air-space walls

versus full-term infants

(20.1 μm vs 12.1 μm)

- 42% of lung volume

versus full-term infants

(75 mL vs 180 mL) - 34% of the lung surface area

versus full-term infants

(1.55 m2 vs 4.55 m2)

- 52% lung volume

versus full-term infants

(93 mL vs 180 mL) - 45% of the lung surface area

versus full-term infants

(2.03 m2 vs 4.55 m2)

Study Design

Normal lungs were obtained from 42 infants (29 liveborn and 13 stillborn) younger than 1 month of age coming to autopsy at Winnipeg Children's Hospital, Winnipeg, Manitoba, over a period of 3 years. Infant age (expressed as gestational age plus postnatal age) ranged from 19 weeks gestation to 3 weeks postnatal age. The lung structures studied were air spaces (saccules or alveolar ducts and alveoli); air-space wall (alveolar and/or saccular); conducting air (lumen of bronchi and bronchioles); and nonparenchyma (all other structures).2

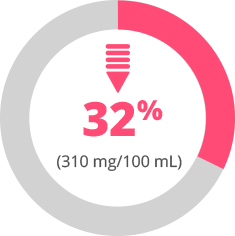

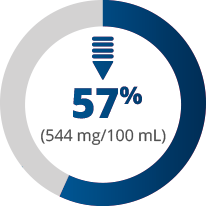

Low serum antibody (IgG) levels place very preterm infants at high risk for severe infection and mortality3

The lower the gestational age, the lower the serum antibody (IgG) levels.3†† Lower serum antibody levels among very preterm infants, especially in the first 6 months of life, may explain their high susceptibility to infection.4

Infants born at 28-31 wGA have

less than 1/3

the serum antibody levels of full-term infants

Very Preterm

(28-31 wGA)

Preterm

(32-35 wGA)

Full term

(≥37 wGA)

††Full-term infants in this study had a mean serum antibody level of 954 mg/100 mL; this was the reference level and was considered to be 100%.3

RSV infection results in significant stress on already compromised very preterm infants.3,4

Study Design

Random serum samples of 182 babies of normal weight for gestational age ranging from 24 to 40 weeks were studied. Blood samples were obtained within 24 hours of birth from heel pricks or indwelling umbilical catheter inserted for other purposes. Gestational age was estimated from the date of last menstrual period and later confirmed by neurological and electroencephalographic examination whenever possible.3

BPD=bronchopulmonary dysplasia; ICU=intensive care unit; RSV=respiratory syncytial virus; RSVH=respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization; wGA=weeks gestational age.

REFERENCES: 1. Packnett ER, Winer IH, Larkin H, et al. RSV-related hospitalization and outpatient palivizumab use in very preterm (born at <29 wGA) infants: 2003-2020. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(6):2140533. doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2140533 2. Langston C, Kida K, Reed M, Thurlbeck WM. Human lung growth in late gestation and in the neonate. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129(4):607-613. 3. Yeung CY, Hobbs JR. Serum-gamma-G-globulin level in normal premature, post mature, and “small-for-dates” newborn babies. Lancet. 1968;1(7553):1167-1170. 4. Pickles RJ, DeVincenzo JP. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its propensity for causing bronchiolitis. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):266-276. 5. SYNAGIS (palivizumab) [prescribing information]. Waltham, MA: Sobi, Inc. 2021. 6. The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102(3):531-537.

All imagery is for illustrative purposes only.